Fictionalising fact: how a folk legend was re-imagined into a pop culture icon

Ned Kelly, in life, as in death, was a polarising figure. During his outlawry Ned became an adversary to the establishment but a crusader to the common folk. When he rode the trails of North East Victoria it was the fight for land between squatter and selector that drew the battle lines. Regularly, Ned’s portrayal in the media shifted through many conflicting attitudes. Metropolitan newspapers squared off against illustrative publications, parochial news sheets, and the ever-popular ‘penny blood’ – cheap publications aimed primarily at young working-class readers that remained popular for most of the 19th and well into the early 20th century. The penny bloods [or dreadfuls, as they were also known] were the predecessors of the illustrated comic.

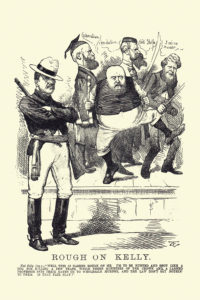

The starkly contrasting opinions voiced in these diverse publications fuelled the public’s awareness of Ned Kelly’s exploits and opened them up to further interpretation. Newspapers of the day competed, criticised, and openly lampooned each other by any means necessary, including their use of Ned Kelly—although none of them could accurately nail down his likeness. For example, a politically motivated illustration in early 1879, while Ned and his Gang were still at large, appeared in the Melbourne Punch. Created by Thomas Carrington, the cartoon shows a beardless Ned Kelly dancing around a ‘communism’ banner with the Victorian Premier Graham Berry and a woman representing The Age newspaper [Figure 1].

Government-issued images printed on wanted notices, often doctored from prison photos taken years earlier, added to the inaccurate depictions. The photographic halftone, today used to reproduce photographs in print, was first patented in 1882, two years after Ned’s death. This lack of a definitive likeness was further fuelled by the metropolitan newspapers, whose artists enjoyed unfettered latitude to portray a stereotypical, bearded bushranger to act as a Ned Kelly proxy. The widespread uncertainty about Ned’s appearance allowed the Kelly Gang to evade capture for over eighteen months, and as time passed, anticipation about his ‘real’ appearance grew to the point of a national obsession.

These often highly imaginative illustrations help set Ned up as a nefarious arch-criminal and aided in the creation of a visual reference for what polite society deemed to be the under or criminal classes. This baseline could be arrayed against controversial figures, such as in the 1879 cartoon ‘Rough on Kelly’. Produced by Thomas Carrington, the image shows three ministers from the Victorian Government and an academic who were accused of inciting ‘wholesale murder’ being admonished by Ned Kelly, who tells them, ‘Is that fair play?’ Yet, at the same time that Ned was being ostracised in certain circles, he was also being lauded by others as knowledge of his activities and motivations spread. Both the portrayals of the man and the descriptions of his exploits impacted his supporters, and together, these helped generate sympathy for Ned’s so-called ‘insurrection.’ They also contributed to forming the basis of his folkloric ascension—for it was these biting whimsies that influenced Kelly’s own perceptions of his self-image and helped him and his followers to believe that the Kelly Gang was capable of intervening in what they saw as corruption and misrule throughout the entire colony.

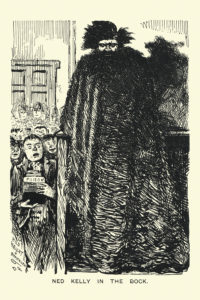

The Melbourne Punch, which ran from 1855 to 1925, was a periodical that could swing left or right depending on the opinion of the day. When Ned’s trial came about, it was firmly in the anti-Ned camp. In late August 1880, a month after his capture at Glenrowan, Ned fronted the Beechworth Court for a preliminary hearing. Artist Julian Ashton recorded Ned’s image for The Illustrated Australian News as an imposing figure with a defiant stare as he grips his suit’s lapel. At the exact same hearing, the Melbourne Punch’s illustrator Thomas Carrington [although strangely attributed to David Gaunson] depicts Ned as a wild creature wrapped in a possum fur as a nearby supporter clutches a jar of poison [Figure 2].

The institutionalised publications and their upper-class masters viewed Ned Kelly and his ilk as nothing more than the dregs of society. Even after his Supreme Court trial and the sentence of death, when 32,000 signatures were collected for a reprieve from execution and presented to the Governor of Victoria, the pleas were simply ignored. While the document represented over 10% of the total population of Melbourne, the petition for clemency was belittled by the ruling class, with the signature’s owners being labelled as nothing more than ‘vagabonds and ruffians.’

The Government wanted Ned Kelly hanged and forgotten as soon as possible. And, by the end of 1880, the mortal Kelly Gang was no more. However, what was left behind was the spark of folklore, which, nearly 140 years later, we see, on average, a Ned Kelly-related story published weekly somewhere around the world. There are over thirty-one million pieces of information about Ned Kelly and the Kelly Gang available online. Ned has been commemorated through plays, music, words, paintings, and film. More books, songs, and websites have been written about Ned Kelly than any other Australian figure — alive or dead. When you factor in the wide variety of Kellyana to the mix—such as tourism, clothing, food, toys, alcohol, souvenirs, etc.—the business of being a folk hero has evolved into a multi-million dollar enterprise—Ned Kelly Incorporated.

Ned Kelly played a significant role in the advent of modern popular culture. The Story of the Kelly Gang, produced in 1906, was hailed as the first continuous narrative film of any significant length worldwide [Figure 3]. Premiering on Boxing Day in 1906 at Melbourne’s Athenaeum Hall, the film was six reels long, or close to sixty minutes in length, a duration that was unheard of at that time. It ran to full houses for five weeks before moving to other Melbourne theatres. It screened in Sydney and Adelaide and toured Queensland. It was shown in New Zealand and England, where it was promoted as ‘the longest film ever made.’ It is interesting to note that between 1906 and 1912, Australia produced more feature-length films than Britain or the United States of America. However, whilst the Australian public took a liking to bushranger stories, the New South Wales police certainly did not and the production of films about bushrangers was banned in 1912. The embargo effectively hamstrung the Australian film industry, in part helping clear the way for Hollywood’s eventual domination.

With the restriction of the local films, advocates for Ned returned to print, and Kelly’s literature began in earnest. Titles like Iron Ned Kelly and his Gang caught the attention of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who, during the Great War, petitioned the London War Office for ‘Kelly Armour’ to protect the troops. In advocating artificial protection for British soldiers, Doyle announced, ‘When Ned Kelly walked unharmed before the Victorian police rifles in his own hand-made armour, he was an object-lesson to the world. If an outlaw could do it, why not a soldier?’ Doyle believed, ‘The use of armour is possible for the protection of the vital parts of a soldier’s body, and ought to be supplied to stormers, whose business is to cross “no man’s land”, attack the machine-gunners, and clear the way for the infantry.’

This fresh interest in Ned encouraged more publications, and in 1929, the first major pro-Kelly work was released. Up to this point, the dominant, mainstream anti-Kelly literature portrayed a ruthless criminal, a symbol of the remnant Irish patriotism loathed by the colonial Victorian government. At the same time, the image of the popular hero was kept alive in oral tradition and folk songs. J.J. Kenneally’s The Complete Inner History of the Kelly Gang and Their Pursuers was the inspiration, in 1946, for Sidney Nolan’s culturally significant Ned Kelly series of paintings.

These works became the most remarkable sequence of Australian paintings in the 20th century. Nolan’s depiction of a starkly simplified Kelly in his bush-made armour has become iconically Australian, culminating in the opening ceremony of the 2000 Sydney Olympics, where many performers donned stylised costumes based on Nolan’s distinctive imagery.

This starkly contrasted with the last time Australia hosted the Olympics in 1956. Back then, Australian poet Douglas Stewart’s theatre production Ned Kelly, starring Leo McKern, was supposed to be included in the Melbourne Olympics list of events – but it was removed due to concerns over projecting the wrong image to the world. Stewart originally published the play in 1946, the same year Nolan started work on his Kelly series. The book featured eighteen impressive pen and ink sketches from another famous Australian artist, Norman Lindsay [Figure 4]. Since then, several plays have been themed around Ned’s story, including Reg Livermore’s rock opera Ned Kelly, which was staged in 1978.

The mythology surrounding Ned Kelly also extended to indigenous dreaming. In 1988, at the Charles Strong Memorial Lecture, anthropologist Deborah Bird Rose discussed two Aboriginal Dreamtime stories about Ned from the Victoria River District of the Northern Territory under the title Ned Kelly Died For Our Sins and further expanded on these accounts in her book Dingo Makes Us Human (1992). Rose explains that the Yarralin people tell a story in which Captain Cook [a metaphor for the deleterious colonial relationships between white settlers and the aboriginal people] took Ned Kelly back to England, where his throat was cut. The story, translated from Kriol by Rose, continues, ‘They bury him. Leave him. Sun go down, little bit dark now, he left this world. BOOOOOMMMMM! Go longa top. This world shaking. All the white men been shaking. They all been frightened.’ Rose argues that, in the same way that Captain Cook came to represent the oppressive side of white settlement, the Kelly story has been conflated with Jesus and all those who stand against oppression and injustice: ‘Aboriginal people in the Victoria River District have not found Ned Kelly to be ambiguous. They have analysed his actions and defined him as purely moral. Through Ned Kelly an equitable social order, which includes Europeans, is established as an enduring principle of life.’

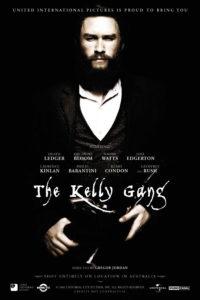

To date, eight significant films have been produced featuring Ned Kelly as the main character, including the 1970 movie Ned Kelly featuring Mick Jagger in the lead role. The Rolling Stones lead singer required armour made from aluminium as Mick could not carry the weight of a set made from iron. At least Jagger was around the right age, as many previous films featured actors who were ‘burly 40-something of unspecified origins.’ In 2003, the late Heath Ledger starred as the bearded outlaw in Ned Kelly [Figure 5]. Adapted from Robert Dewe’s book Our Sunshine, the film was described as ‘Young Guns in armour’ although the Academy Award winner did an impressive job channelling Ned Kelly. Ledger was near the same age and height and was reported to have immersed himself in the lead role.

On the ‘small screen,’ the stand-out TV production was and still is Ian Jones and Bronwyn Binns’ 1980 eight-hour mini-series The Last Outlaw. The series starred a young John Jarratt [of Wolf Creek fame] along with Sigrid Thornton, Steve Bisley [Mad Max], Gerard Kennedy, Julia Blake, and Lewis Fitz-Gerald. It told the Kelly story in one of the most physically accurate and meticulously researched portrayals. The Last Outlaw examines the life of Ned Kelly and expounds the legend from early indiscretions and gang formation through to the violent shootout at Stringybark Creek, culminating in his explosive last stand and fiery end at Glenrowan. Directed by Kevin James Dobson and George Miller [Mad Max franchise] with music by Brian May, the Logie award-winning four-part special was filmed on location in and around Kelly Country.

From film and paintings to print, where penny bloods, penny dreadfuls, pamphlets, and periodicals held a fascination for the story of Ned Kelly. Even before his demise, four dedicated publications were already in print, including the tongue-in-cheek The Book of Keli, published in mid-1879 by George Wilson Hall. While each story varied as much as the quality of the publication and facts mixed liberally with fiction, a superhero archetype emerged with each re-telling. When publishers added the excitement of illustrations to the mix, the resulting narratives became a visual attraction eagerly consumed by old and young alike.

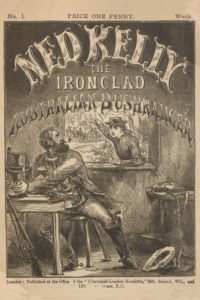

In 1881, just a year after Ned’s execution, a compilation of a thirty-eight-part weekly series titled Ned Kelly the Ironclad Australian Bushranger—written by James Borlase but credited as being by ‘One of His Captors’—was published by Alfred J Isaacs and Sons of London, helping bring Ned’s notoriety to the English public [Figure 6]. Noted Australian banker and historian H.G. Turner described the series as ‘a gory compilation of melodramatic impossibilities’ which aligned perfectly with the penny blood ethos of presenting dramatic tales and outlandish storylines concerning pirates, adventurers, and villains to a working-class public hungry for cheap, long-lasting and value for money entertainment.

So, kicking and screaming, the pulp fiction version of Ned Kelly was born. Writers and publishers chose which parts of the ‘real’ story they would use and what sections would be ‘romanticised’, and the story was perpetuated in dozens of variations. Folklore became intertwined with historical facts [and vice-versa] just as in the children’s party game Chinese Whispers or, as it is known in the United States, the Telephone Game. Tens of thousands of copies of the Ned Kelly story, in one guise or another, were sold in Australia, the United Kingdom and several Commonwealth countries, including New Zealand and South Africa. In 1938, when Action Comics #1 introduced Superman, Ned Kelly was not far behind. Published around 1940, The Kelly Gang Rides was a juvenile comic strip that presented a Westernised version of the Kelly story and even had Ned dressed in 1940s-style clothing.

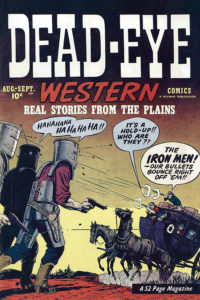

It is documented that Ned Kelly and his lieutenant Joe Byrne’s decision to build the armour was influenced by two international factors: Ned’s favourite book, Lorna Doone – where the outlaw Doones were described ‘with iron plates on breast and head’, and by a visiting display of Chinese armour shown in the late 1870s at Beechworth. Conversely, the Kelly Gang armour has influenced several international publications, including many comics based on America’s Wild West. The cover of Dead Eye Western #11, published by Hillman Periodicals in 1950, appears to be an interpretation of the siege at Glenrowan between the Kelly Gang and the police [Figure 7]. The cover is particularly well rendered, and whilst the story is convoluted, the origin of the armour is indisputably Ned’s.

The now common trope of the anti-hero armoured up against a range of ‘good guys’ includes the 1952 edition of Tim Holt #32, in which the protagonist faces off against a colourful character known as Iron Mask. Ten years later, in 1962, we get Marvel’s Stan Lee and Jack Kirby’s character Kid Colt unsuccessfully battling another villain, also named Iron Mask. This made the Iron Mask Colt’s arch enemy—a novel move given that the norm of the day required that criminals were generally dispatched within a single episode.

However, the bulkier armour on the cover of Kid Colt Outlaw #114 is a better representation of Ned Kelly’s compared to the flimsy and lightweight protection Iron Mask wore in his debut issue #110. Comparing the armour, it’s not inconceivable to see a parallel in the character’s design with publisher Stan Lee’s other hero, The Invincible Iron Man, particularly the Mark 1 suit. Iron Man first appeared in Tales of Suspense #39 [March 1963], only months after Marvel’s Iron Mask first battled Kid Colt.

Fast forward to the new millennium, and we meet the Swagman, a DC supervillain who borrows heavily from the Ned Kelly mythos [Figure 8]. The Swagman’s first appearance was in Batman #676, and, as the name suggests, he began his criminal career in Australia. This quickly brought him into conflict with the Dark Ranger, an ally of Batman—Swagman protect himself by wearing different types of makeshift armour while brandishing swords and grenade launchers. Although the Swagman is not a regular in the Batman universe, he appears in the episode The Knights of Tomorrow! in the animated series Batman: The Brave and the Bold [2008-2011].

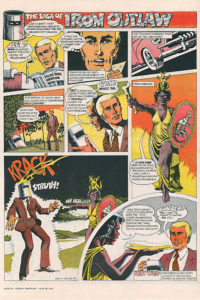

Back in Australia, in June 1970 the politically incorrect comic Iron Outlaw commenced in Melbourne’s Sunday Observer. Written by Graeme Rutherford and drawn by Gregor MacAlpine, Iron Outlaw sometimes ridiculed but mostly poked fun at the political and social institutions of Australia, setting about the ‘Ocker’ image with great relish. At the same time, Rutherford and MacAlpine highlighted the popularity of comic book super-heroes, particularly the characters from Stan Lee’s Marvel Comic Group and imitated the styles of well-known comic book artists, (such as Neal Adams), to reinforce their point. The alter ego of Iron Outlaw was Gary Robinson, then a junior accountant for the Melvern City Council in Victoria, who said he was tormented by the injustices he witnessed against the citizens of Melbourne [Figure 9].

On a visit to Glenrowan, Gary finds an old Ned Kelly-style helmet and wishes that he had the strength and courage of Ned Kelly to combat the forces of evil. From nowhere appears Yum Yabbi, the spirit of the bush and an Aboriginal answer to Britannia. With a winged kangaroo perched on her head, an Aboriginal kangaroo motif on her shield, she points a bone at Gary and by uttering the magic words ‘Ah hoo la la’ she transforms him into a super being and presents him with a pair of golden boomerangs. Gary thinks it is ‘Bonzer’.

In typical superhero fashion, Iron Outlaw soon gained an off-sider in the form of Steel Sheila, who is Dawn Papadopolis, a council typist. Together they ride the countryside in Iron Outlaw’s orange FJ Holden with mag wheels and a broad GT stripe. Early stories were restricted to Melbourne, where they mercilessly caricatured Sir Henry Bolte, the then Premier of Victoria, as ‘Humpo – The Hunchback of St Paul’s’, a man who is determined to spread doom and gloom by making every day like a Melbourne Sunday. When the duo were ‘called upon’ by Prime Minister John Gorton to serve their country, the strip quickly broadened its horizons beyond Melbourne and opened up a whole new field for satire.

Several episodes involved the Prime Minister, then William McMahon, as the super-hero Kokoda Kid—complete with a digger hat and a chest full of medals. The strip kidded the conservative reputation of Melbourne in a panel where Steel Sheila was changing out of her costume. A text box was added to read, ‘In deference to our sensitive Victorian readers, Dawn appears nippleless. ‘

With the closure of the Sunday Observer imminent, Iron Outlaw and Steel Sheila [as the strip was now called] transferred to the pages of the Sunday Review in February 1971. While it went from colour to black and white, the strip hit its visual peak with some stunning artwork by MacAlpine on a story about the Yellow Peril featuring Madam Loo and Warlord Nong. By the time it had finished in June of the same year, the comic had satirised everything in sight and, in the process, confronted readers with some of the more unpleasant aspects of our society. In the final story, Iron Outlaw becomes the dictator of Australia and imprisons the incredulous Steel Sheila – after all, she was only a ‘little wog!’ Greg and Grae, as they by-lined themselves, moved on to other fields, and the world of comic strips was poorer because of their leaving.

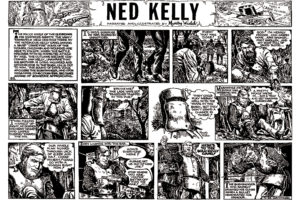

Since then, although there have been many illustrative interpretations of the Ned Kelly legend, none have been as detailed or authentic as Monty Wedd’s version from the mid-1970s [Figure 10]. The original plans for the comic strip called for Ned Kelly to run for twenty-five to thirty weeks, but when Wedd sensed the opportunity to produce a detailed examination of Kelly’s life, he approached the Sunday Mirror in early 1974 and explained what he had in mind. They agreed he should draw the comic open-ended, so Ned Kelly ran weekly for one hundred and forty-six weeks in several of Rupert Murdoch’s Australian newspapers, finishing in July 1977. Apart from the standard research that would go into a comic of this nature, Wedd visited the courtroom and various other spots to make the strip as authentic as possible. He told the story with an even-handed approach and left it to the reader to determine Kelly’s rightful place in our history. Rendered in a style that resembles earlier engravings, with considerable crosshatching, the comic remains an excellent example of using the medium of comics to teach history.

The Weekend Australian described Monty’s Ned Kelly work as such, ‘Wedd’s lucid, meticulously researched narrative is never less than engaging, while his sharp visuals and densely detailed storytelling bring a persuasive clarity to his account of Kelly’s life. A unique and worthy inclusion in the ever-expanding Ned Kelly canon. The strip’s studied period vernacular and antiquated design reinforce the illusion, capturing the appearance and tone of illustrated Victorian pamphlets. An accomplished draughtsman, Wedd effortlessly blends an expressive cartooning style with intricate cross-hatching that emulates the look of 19th-century engravings. He readily uses cinematic flourishes when the occasion demands, such as the exciting, impressively staged Stringybark Creek and Glenrowan set pieces. The latter vividly conveys the chaos, farce, tension and pathos of the confrontation. That he achieves this while observing the conventions of a serialised comic strip, with its recaps and cliffhangers, is testimony to his skills as a graphic storyteller.’

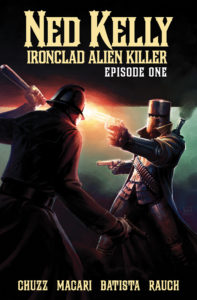

Moving from newspaper strips to dedicated comic books utilising digital publication and distribution, Convict Comics’s 2016 steampunk-styled mini-series Ned Kelly: Ironclad Alien Killer is a fictionalised comic book that centres on how Ned Kelly defeated an alien invasion and escaped the hangman’s noose [Figure 11]. In the mid-1800s, Earth was colonised by aliens who landed in the Australian outback and utilised masking technology to disguise themselves as humans. They then infiltrated the highest levels of society in the new colony of Victoria.

The resistance movement was formed by inventor Henry Sutton, a real-life Australian genius who invented early versions of the telephone, the light bulb, the television, and the aeroplane. Sutton provides the technology necessary to fight the aliens and recruits Ned Kelly to lead the charge. The work is a collaboration between Marvel and DC comics veterans, including Chris Batista, John Rauch, and David Meikis.

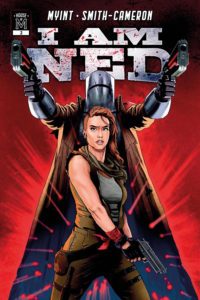

Publishers like Convict Comics and the House of M are well aware of the significance of public consciousness. They understand that if you have a ready-made character with which an audience can empathise, in the case of House of M’s alternative universe Ned Kelly in their series I AM NED, much of the hard work is already done.

By choosing a persona with an existing background, the reader will have a familiarity or affinity with the subject. People who pick up a Doctor Who comic are typically already aware of the narrative and backstory. However, unlike Batman’s seventy-five-plus years of myth, House of M did not have the luxury of time or the depth of resources to create and nurture an unknown character to maturity. So, much as Marvel did with Thor, these Australian publishers ‘superman’ was pulled ready made from the pages of history.

Written by Max Myint with illustrations by Zachary Smith-Cameron, House of M’s I AM NED #1 [2017] is set in the wake of World War 4, and what remains of the continents have been isolated from each other [Figure 12]. Australia is now lost to an intelligent species of zombies. For ten years, the oppressive regime known as the ‘Zombie World Order’ has commanded loyalty from its citizens through power and propaganda. People are hunted and sent to ‘human farms’, where they are then portioned and delivered to the hungry masses like cattle. One man dares to stand against the plague. Building armour inspired by the legendary Ned Kelly, he is driven and merciless in his desire to bring down this zombie empire. The world this Ned inhabits is Planet of the Apes in style but with zombies as the dominant species. I AM NED is part Mad Max [1979], 1984 [1984], and V for Vendetta [2005]. It’s unapologetically violent and brutally gory, with dark political undertones and provocative concepts that challenge our perspective of individuality and happiness.

In the almost 140 years since his execution, Ned Kelly has been mythologised as a ‘Robin Hood’ character, been accepted into aboriginal narratives, and become a political icon and a figure of Irish-Catholic and working-class resistance to the colonial and, to some degree, contemporary establishment. The proliferation of illustrated newspapers, made possible by advances in printing technology and cheap mass publishing in colonial Australian culture, was an aspect of the industrial revolution that focused, nurtured and enabled the popularisation of Ned Kelly as a national symbol. Indeed, the pervasive nature of Kelly’s imagery resonated as powerfully in the late 19th century as today. In Kelly’s manifesto, the Jerilderie Letter, Ned commands the wealthy squatters to share their land with and redistribute their wealth to the selectors – the rural poor – for ‘it will always pay a rich man to be liberal with the poor … if the poor is on his side, he shall lose nothing by it.’

For some contemporary commentators, his Letter is comparable to a Marxist proclamation for poor Australian colonists, while reading it has been likened ‘to listening to a radio broadcast by revolutionary Che Guevara.’ Favourable accounts of Kelly from his captives and his ‘public performances’ of burning mortgage documents during his bank raids contributed to his reputation as a man of the people. In his book Outlaw Heroes in Myth and History, Graham Seal writes, ‘Ned Kelly has progressed from outlaw to national hero in a century, and to international icon in a further twenty years. The still-enigmatic, slightly saturnine and ever-ambivalent bushranger is the undisputed, if not universally admired, national symbol of Australia.’ Polarising Kelly may be, however, what remains undisputed is our modern Ned remains a fascinating enigma – he’s a man whose life struggle became folklore, which eventually morphed into mainstream Australian pop culture.

Basu, L 2012, Ned Kelly as Memory Dispositif. Media, Time, Power, and the Development of Australian Identities, Walter de Gruyter, Berlin.

Bird, D 1992, Dingo makes us human. Life and land in an Aboriginal Australian culture, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne.

Bolle, F 1952, Tim Holt #32, Magazine Enterprises, New York.

Borlase, J 1881, Ned Kelly the Ironclad Australian Bushranger, Isaacs and Sons, London.

Carrington, T 2003, Ned Kelly. The Last Stand. Written and illustrated by an eye witness, Lothian Books, South Melbourne.

Chuzz, M and Macari, N and Batista, C and Rauch J 2017, Ned Kelly. Ironclad Alien Killer #1, Convict Comics, Melbourne.

Hall, G.W (ed.) 1879, The Book of Keli, Mansfield Guardian, Mansfield.

Kenneally, J.J 1929, The Complete Inner History of the Kelly Gang and Their Pursuers, J. Roy Stevens Printer, Melbourne.

Lee, S and Kirby J 1964, Kid Colt Outlaw #110 and #114, Marvel Comics, New York.

Myint M, and Smith-Cameron, Z 2017, I AM NED #1, House of M, Brisbane.

Ryan, J 1979, Panel By Panel. An illustrated history of Australian Comics, Cassell Australia, Melbourne.

Seal, G 2011, Outlaw Heroes in Myth and History, Anthem Press. London.

Walton, B 1950, Dead Eye Western #11, Hillman Periodicals. New York.

Webb, B 2017, Ned Kelly. The Iron Outlaw, New Holland Publishers, Sydney.

Wedd, M 2013, Ned Kelly, Comicoz, Margate.