Finding an Australian voice among a chorus of American superheroes

If asked to name a superhero, a person’s likely response would be a character from either the world of Marvel or DC [Detective Comics] — such is the extent of their influence and power. From Spider-Man, The Hulk, and Iron Man to Batman, Superman, and Wonder Woman, these giants of the comic book industry seemingly possess a limitless ability to churn out ‘super’ personalities at an alarming rate, flooding the world with goodies [and baddies] through a multitude of expanded universes and alternative realities.

Seemingly, every corner of the world has been allocated their own particular [and occasionally, peculiar] superhero or villain. Many of these early adopter archetypes were a conglomerate of racial and sexual clichés whose genesis can be traced back to the mid-twentieth century—a time of fervent bigotry and xenophobia. One such example is ‘The Ancient One’, the vaguely sinister occasional mentor of Marvel’s Doctor Strange [Figure 1.0]. Up until the late 1980s, this male Tibetan mystic was represented, in one form or another, as a stereotypical Asian whose exaggerated features borrowed copiously from illustrations that featured in Western culture drawn from the dark days of the Korean and Vietnam Wars.

However, to placate a growing Asian consumer market, particularly China’s expanding cinema audience, Marvel announced that in the movie Doctor Strange [2016], The Ancient One would be played by Tilda Swinton, a Caucasian female. Decried by many in the West as an act of ‘whitewashing’, a statement from a Marvel Studios spokesman defended the hiring of Swinton:

Marvel has a very strong record of diversity in its casting of films and regularly departs from stereotypes and source material to bring the Marvel Cinematic Universe [MCU] to life. The Ancient One is a title that is not exclusively held by any one character, but rather a moniker passed down through time and, in this particular film, the embodiment is Celtic. We are very proud to have the enormously talented Tilda Swinton portray this unique and complex character alongside our richly diverse cast.

Rosenberg

Marvel’s statement appeared to be a measured response, essentially saying The Ancient One is more a title than an individual persona, so Tilda Swinton, an Anglo-Scottish-Australian, establishes a new character vision. Also responding to several critics who suggested The Ancient One should have been played by a Tibetan or Chinese actor, Doctor Strange co-writer C. Robert Cargill contends that The Ancient One’s comic book origins are rooted in racist stereotypes, which makes it impossible to avoid controversy when bringing the character to the big screen.

He originates from Tibet, so if you acknowledge that Tibet is a place and that he’s Tibetan, you risk alienating one billion people who think that that’s bullshit and risk the Chinese government going, “Hey, you know one of the biggest film-watching countries in the world? We’re not going to show your movie because you decided to get political.” If we decide to go the other way and cater to China in particular—if you think it’s a good idea to cast a Chinese actress as a Tibetan character, you are out of your damn fool mind and have no idea what the fuck you’re talking about.

Rosenberg

Closer to home and, once again, thanks mainly to American ink, Australian characters from the Marvel and DC universe appear as increasingly stereotypical genre-based ‘ockers’—their roles are usually clichés, typecast, or frequently both. While a grateful United States adopted DC’s clean-cut superhero Superman, Australia was ‘blessed’ with the supervillain George ‘Digger’ Harkness, better known as Captain Boomerang [Figure 1.1]. Created by John Broome and Carmine Infantino, the Captain first appeared in Flash #117, December 1960. As the nemesis of The Flash, resplendent in a ludicrous blue smock emblazoned with boomerangs and sporting an airline hostess-style cap, Digger’s appearance was designed to elicit a sense of terror in Barry Allen [Flash’s alter-ego], however, for an Australian reader, it likely evoked fits of laughter.

Besides the stereotypical ability to throw boomerangs, the good Captain was also prone to bouts of racism—in several editions of Suicide Squad, ‘Digger’ Harkness would refer to black team member Bronze Tiger as an ‘abo’. With such a mountain of clichés piled onto Captain Boomerang’s shoulders, it’s surprising he never gained his powers from downing a can of beer [in the same way Popeye derived his strength from spinach]. In the 2016 big-screen adaptation of Suicide Squad, Captain Boomerang was at least portrayed by an Australian actor, Jai Courtney. The character still successfully managed to fulfil his stereotype quota, as the Aussie beer-swilling ocker, by downing countless cans of golden ale. Even amid a war-ravaged city, it’s pleasing to think there are still places to get an ice-cold beer. Thankfully, Courtney’s costume was sans blue smock.

Not to be outdone in the uninspiring comic character stakes, Marvel also produced their Australian supervillain by the name of—wait for it—Boomerang! Created by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, Boomerang made his first appearance in Tales to Astonish #81 in July 1966. Boomerang’s abilities include being a world-class baseball pitcher [but no mention of cricket], a skilled marksman and a street fighter. Naturally, the character wields a variety of lethal and gimmicky boomerangs; however, he also manages to fly with a handy pair of jet boots. Boomerang is constantly pitted against Spider-Man and comes out worse for wear regularly. Frederick ‘Fred’ Myers [Boomerang’s alter-ego] was born in Alice Springs and raised in the United States [Figure 1.2]. This may explain how Fred went from speaking with an American accent to an Australian one when he grew up [actually, no, it doesn’t].

I told them I was born in Australia, so they made me Boomerang. This is why the whole world hates you, by the way. An entire nation boiled down to what you can remember from that time you got high and watched Crocodile Dundee. Guess I should be glad I didn’t end up some kinda kangaroo guy…

Boomerang The Superior Foes of Spider-Man #1

Relying on writers and illustrators from countries like the United States to determine what guise Australian superheroes and villains take goes a long way in explaining why Australia has no relatable characters. How can a reader sympathise with, or respond to, a character they cannot identify with on a fundamental level—that of being Australian? Discounting America-centric bias, it is understandable, seeing every major publication now originates from the United States. Actual homegrown characters are scarce indeed. For a while, Australia has adopted characters like The Phantom and introduced storylines relevant to our region, publishing titles and making territory-specific stories that boil down to pure economics. Will it sell?

And what about collaborations? Some fine Australian artists and writers have worked for multinational publishers inside teams developing comics with an Australia-centric theme or circumstance. With someone on the ‘inside’, what could go wrong? Many of these projects originate in boardrooms far removed from the talent pool. The creative team is usually presented with a detailed synopsis, storyboard, or script; timelines and narrative arcs to develop and maintain; and, occasionally, a convoluted plot, back story or future self that needs to be integrated into the current assignment. Creative expression and freedom to explore are subjects rarely associated with DC, Marvel, or other large comic enterprises. Homegrown talent is no guarantee that a ‘down under’ themed comic produced in the United States will resonate with readers in Australia. And with their eyes firmly set on the American, United Kingdom and emerging Chinese markets, why would an editorial team deliberate the finer issues concerning cultural or historical accuracy? After all, it’s just a comic book. Who cares if they insult a few Antipodean sensibilities?

While the level of artistic capability, primarily the dexterity of detail, and the paper and print quality of comics have improved significantly over the past thirty years [Katz, 2014], the storytelling transformation has slowly evolved. Although casual racism and sexism have essentially been removed from today’s comic books [unless the script calls for an antagonistic villain], storylines set in ‘exotic’ places abound with presumptions and clichés. A popular destination for comic storylines is Australia (primarily Sydney), along with outback scenes depicting the Aussie lifestyle as envisioned by Paul Hogan’s Crocodile Dundee [1986]. In October 1988, DC Comics Inc. released Detective Comics #591 Aborigine! [Figure 1.3] pitted Batman against Umbaluru, an Indigenous Australian who had travelled to Gotham City to seek the return of a stolen artefact known as the ‘Power Bone of Uluru’. Featuring a storyline with more than a few parallels to Crocodile Dundee II [1988], when Mick moved to Manhattan with his girlfriend, Umbaluru is powered by the ‘Earth Mother’ who seeks revenge for the murder of the Bone’s indigenous guards. The writers were undoubtedly conscious of Australia and had investigated some indigenous creation stories. The first few pages touch on The Dreaming, which helps link the story of the Bone to the comic’s narrative. There’s even a mention of the 1988 bi-centennial with a shop window display that gets vandalised by Umbaluru near the end of the story. He changes ‘Happy 200th Birthday Australia’ to ‘Happy 50,000th Birthday to the People’.

The composition of the Umbaluru character is a relatively accurate depiction. However, as a stand-alone comic, there’s little room to develop his personality beyond the one-dimensional, seek and destroy, Terminator figure. Yet, while the concept is commendable, the execution smacks of uninformed racism. Unlike DC’s other indigenous character, The Dark Ranger, with his educated, urban background, Umbaluru is cast as ‘the naked Central Australian with a limited understanding English styled trope which is so often employed by writers, despite the vast majority of us being from the coast, and living in cities and major regional centres’ [Koori History, 2016]. Umbaluru is constantly referred to as an ‘Abo’, and in one panel, an antagonist yells, ‘Stinking primitive – that’ll teach you’ as he attempts to bash Umbaluru’s skull with a hammer. Umbaluru is also referred to as ‘the aborigine’, both in the comic and again online on the DC Database wiki page. Granted, Aborigine! was published in 1988, but the character of Umbaluru has not been seen since. The contributors to DC’s wiki page would most likely be unaware of ‘the negative connotations the use of Aborigine[s] or Aboriginal[s] has acquired in some sectors of the community, where these words are generally regarded as insensitive and even offensive’ [School of Teacher Education, 1996 p.1].

By the end of the comic, Umbaluru prevails, throwing the main villain out of the window of a skyscraper, but not before he fights Batman [Figure 1.4], who’s keen to see Umbaluru answer for his crimes of murder in a court of law. This doesn’t end as planned for the Dark Knight, with Umbaluru telling him, ‘White man’s justice? For an Aborigine? Where have you been past two hundred year?’

Undoubtedly, the writers at DC attempted to portray Umbaluru in a sympathetic light. Even Batman gives pause during their final confrontation when he learns the truth about the fate of the Bone’s Uluru protectors. However, Batman’s sense of justice compels him to bring Umbaluru down. That Batman is ultimately unsuccessful raises the question of who prevailed over this confrontation and what lesson, if any, was learnt. Umbaluru successfully manages to regain the ‘Power Bone’ while exacting bloody revenge on those who murdered his brothers. Batman is left brooding on a rooftop while the narrator observes, ‘By his account, the men the aborigine killed deserved to die. And perhaps they did. But he can make no allowance for righteous murder. All killers must be brought to book’. That is a nice sentiment, except Umbaluru did escape; his mission was a success. An Aussie outsmarted the world’s greatest detective. Chalk up a win for the away team.

America has shown a fondness for utilising Aboriginal Australian characters within the US comic industry and their limited attempts at depicting diversity, but it’s not alone in such attempts. The Japanese manga series Silent Möbius is home to Tokyo police officer Kiddy Phenil, a redheaded Aboriginal woman with cybernetic implants.

Koori History

In Marvel’s 2005 series The Incredible Hulk [Figure 1.5] [Volume 2 #83–85], supervillain Exodus rules Australia, assisted by Pyro and the Vanisher. They see humans as nothing more than servants. This brings them into conflict with the Hulk’s alter ego, Bruce Banner, who lives in the Australian outback. Banner has found a peace he’s never known amongst a tribe of Aborigines—they even bestow the name ‘Two Minds’ onto him [even though this naming custom is closer aligned to Native America]. But the Hulk is forced to intervene when their safety is threatened by a battle orchestrated by the ruling totalitarian mutant government. He attacks the President [no Prime Ministers here!], taking Exodus out and claiming leadership over all of Australia [Chez, 2009].

As an Australian, the whole series is a four-part WTF? moment. The story was written by Peter David, an American seemingly influenced by Steve Irwin’s The Crocodile Hunter. In one scene, the Hulk says ‘G’Day’ as he wrestles five enormous predatory semiaquatic reptiles. The Indigenous population, central to this narrative, are portrayed as a cross between a grass-skirt-wearing Polynesian and a nineteenth-century head-hunter from the New Guinea highlands. The Sydney Opera House is also featured in this story arc [the Hulk destroys that, too, as he doesn’t like opera]. This is just one example where multinational comic publishers portray Australia as a destination and its inhabitants as nothing more than pawns or extras. No attempt by any of these corporations to create an Australian-based superhero exists. What’s the point? If Australia gets into trouble, America can send one of its superheroes to sort out our problems. Is this simply art imitating life?

Comics often parallel other avenues of entertainment. Up until the late twentieth century, many Australian characters were depicted in American cinema and television using American or British actors attempting Aussie accents and lingo, to laughable and often cringeworthy results [think Meryl Streep as Lindy Chamberlain in A Cry in the Dark, 1988]. Many of those characters drew on conservative and anachronistic stereotypes that did not represent or reflect the cultural, ethnic and racial diversity of contemporary Australia. Thankfully, the entertainment industry has begun to embrace multiplicity—primarily driven by customer demand wrought partly by social media strategies. One such campaign was aimed at the video game Mad Max [2015]. Produced by Avalanche Studios [Figure 1.6] for worldwide release, this open-world action-adventure was based on the Mad Max franchise. Still, the storyline was not directly connected to George Miller’s Mad Max: Fury Road [2015].

The initial beta release had the lead character Max Rockatansky speak with a ‘generic’ American accent. When Stephen Farrelly, a writer and editor with the website www.ausgamers.com, asked the developer why, he was told: ‘Because we’re trying to create our own vision.’ Farrelly was incensed. ‘Max is such an iconic Australian character, it’s wrong to do that. And they’ve recreated that iconic Australian car, the XB Ford Falcon Interceptor, even down to it being right-hand drive, so why change the character? [Quinn, 2013].’ The voice was changed to an Australian accent due to an online petition and a horde of angry gamers [myself included] venting their displeasure on the developer’s social media platforms.

It was a case of history repeating. Despite the international triumph of the original Mad Max [1979], when the movie was released in the United States, its distributor, American International, wrongly believed their audience incapable of understanding the Australian language, so they had it crudely dubbed by American actors. This version removed all the Aussie slang, significantly altering the movie’s overall ‘feel’. Coupled with a poor marketing campaign, Mad Max failed to get the audience it deserved inside the United States despite its colossal success everywhere else [Harper, 2014].

When Mad Max 2 [1981] was released, Warner Brothers picked up the American distribution rights and changed the title to The Road Warrior. Unaware of the impact this Antipodean pop culture phenomenon, with its original Australian soundtrack restored, had made in the United States through cable television, they mistakenly believed Americans knew nothing of Mad Max. The movie initially suffered from low attendance until word got around that it was Mad Max 2. Subsequent DVD and Blu-ray releases have reverted to the original Australian titles. Again, it highlights that American businessmen do not always know what’s best for their audience.

In 2015, DC Comics released an official mini-series based on the fourth film in the Mad Max saga, Fury Road [Figure 1.7]. The four-part series had a distinctly ‘ girt by sea ‘ feel, written and inked by Australians, with final editing rights overseen by George Miller. While successive movies within the franchise have devolved their Australian origins, the story of Mad Max is still regarded as quintessentially Australian. Mad Max: Fury Road’s story arc was a prelude to the 2015 big-screen production, which bears the same name. The publications received critical and commercial success, but George Miller has no plans to expand the series. While this is disappointing to Mad Max’s millions of fans, it highlights that, if done correctly, there is a market and an audience eager to pay for and consume, on a world stage, Australian pop culture.

In May 2017, a Google search yielded 26,500,000 results for ‘Mad Max’. This vast index included thousands of inspired fan art and cosplay references, bespoke to an audience keen to explore the myth of Max Rockatansky. Yet, surprisingly, Mad Max is a very lean franchise—especially when compared to Disney’s Star Wars juggernaut. The original Mad Max movie first appeared in Australian cinemas in April 1979. It spawned three sequels and a minimum amount of official memorabilia. Dedicated fans have made up the rest—from full-size XB Ford Falcon ‘Interceptor’ replicas to ‘comic book covers imagined for cult movies’ [Quigley, 2010].

Unlike the landscapes that dominate the Mad Max franchise, Australia isn’t a barren wasteland when it comes to superheroes. From Captain Atom to Cyberswine, we’ve had several attempts in the past, and a few even survived into middle age, but all retired far too early. Recent efforts lacked general appeal and, more importantly, a product range. The international heroes have come to dominate the marketplace on the back of significant marketing, which includes, in no small part, merchandise—toys, clothing, and accessories. And it’s not just the big names like Batman and Spider-Man. Lesser-known heroes and villains, such as Ant-Man and Harley Quinn, have pushed themselves to the fore thanks to Marvel and DC-backed blockbuster movies. With each cinematic release, a range of collectables and consumables find their way to department store shelves to be eagerly grasped by frenzied children and collectors alike.

Since the late 1970s, the comic scene in Australia has primarily been driven by self-publishers who have created, printed, and distributed their works. A few publishers, such as Phosphorescent Comics, were willing to publish the work of others, although they have seemingly vanished. From the early 2000s, international publishers began to produce graphic novels by Australian comic creators, starting with The Five Mile Press and Slave Labor Graphics and, more recently, Allen & Unwin [Bruce Mutard’s The Sacrifice and The Silence] and Scholastic. Others, namely Gestalt Publishing [which is acknowledged as Australia’s largest independent graphic novel publishing house], have managed to become professional publishers of Australian comics and graphic novels. While their stable of titles is modest and distribution limited, they have managed to survive against the larger monopolies by clever product placement and a loyal fan base. A recent coup was Gestalt’s contract to produce the Cleverman [Figure 1.8] comic book series, whose television rights were sold to ABC in 2016. Of course, backing up any viable concept with well-executed products and ever-important merchandise helps entertain the public. At the same time, the next episode is being produced and must form any successful long-term business strategy. So, presently, the Australian superhero club membership remains very thin on the ground.

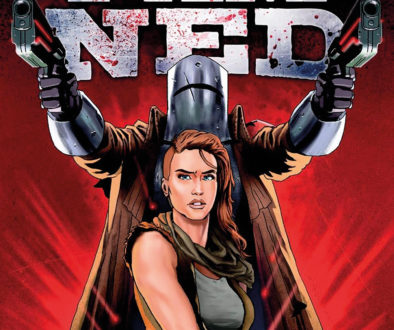

Publishers like Australia’s Convict Comics are well aware of the significance of public consciousness. They understand that if you have a ready-made character that an audience can empathise with, in their case, an alternative universe, Ned Kelly in their series Ned Kelly: Ironclad Alien Killer [Figure 1.9], much of the hard work is already done. By choosing a persona with an existing background, the reader will have a familiarity or affinity with the subject. People pick up a Doctor Who comic as they know the narrative. Unlike Batman’s seventy-five-plus years of myth, Convict Comics did not have the luxury of time or the depth of resources to create and nurture an unknown character to maturity. So, much like what Marvel did with Thor, Convict Comics’s ‘Superman’ was pulled from the pages of history. And while the Ned Kelly: Ironclad Alien Killer series was short-lived [only three issues were released before the publisher switched genre], it did underscore the point that a well-written and illustrated comic can attract an eager readership well beyond our sandy shores.

However, it’s not just American pop culture that impacts Australia. Located in the Asian sphere of influence, globalisation plays a significant role in shaping our international identity. Through preserving traditional folklore and customs via regional culture and a better understanding of how transnational experiences can contribute to developing new-media delivery, recent and emerging publishing technologies can be leveraged to overcome limitations and obstacles encountered by current print and distribution processes. This flow-through of knowledge could ensure the longevity of an indigenous comic-based enterprise and reward Australia with its superhero. But simply making the superhero Australian isn’t guaranteeing a comic book’s success or longevity. Captain America has survived decades because the character continues to be well-written and illustrated, not solely because he’s American. No doubt, regional factors play a part in the success or failure of a character because readers are attracted to exotic locations and storylines. Still, even the Black Panther must leave Wakanda occasionally.

Chez, K 2009, House of M: Incredible Hulk, viewed 19 October 2016.

Google, 2017, Mad Max, viewed 15 March 2017.

Harper, O 2014, Mad Max 2 – The Road Warrior (1981) Retrospective/Review, viewed 12 January 2017.

Katz, E 2014, In general, has comic art improved over the years?, viewed 13 November 2016.

Koori History, 2016, Cleverman – The First Aboriginal Superhero?, viewed 19 August 2016.

Quigley, R 2010, Comic Book Covers Imagined for Cult Movies, viewed 13 September 2015.

Quinn, K 2013, Max mad as Australian accent scrubbed, viewed 9 May 2015.

Rosenberg, A 2016, Doctor Strange’ writer blames China for whitewashing, viewed 27 April 2016.

School of Teacher Education, 1996, ‘Using the right words: appropriate terminology for Indigenous Australian studies’ in Teaching the Teachers: Indigenous Australian Studies for Primary Pre-Service Teacher Education, University of New South Wales, Sydney.

Stewart, D 2017, Why the Portrayal of Australians in Superhero Comics is So Cliched, viewed 17 August 2017.