Who were Australia’s superheroes and where have they gone?

American popular culture has significantly impacted the Australian psyche – from cars, television, cinema, clothing, and food to reshaping the vernacular and written word. After Australia’s Golden Age, it would take another forty years before we had anything resembling a comic book industry. Given the talent and resources available, why aren’t any recent comics worthy of international success?

Until December 1941, when the United States of America entered the Second World War, the Australian comic industry was primarily devoted to reprinting American newspaper strips. To capitalise on reducing supplies from England and America, the local publishing industry initially increased the number of reprints, including Donald Duck and Mickey Mouse, Sergeant Stony Craig, and Alley Oop. However, as overseas artwork was complicated to access due to wartime restrictions, stocks were soon exhausted.

These circumstances led to the creation of original Australian comic books. Such books were written and drawn by local talent. While a significant percentage of this original material was crude in design and amateurish in execution, there were a small group of artists whose work was of a high standard. Anything Syd Nicholls [The Phantom Pirate], Hal English [Red Steele], and Syd Miller [Red Gregory] produced was well worth the purchase price.

The post-war years established some of Australia’s finest comic-book creators. John Dixon [The Crimson Comet], Stanley Pitt [Silver Starr], Monty Wedd [Captain Justice], and Phil Belbin [The Raven] were some of the artists responsible for the ‘Golden Age’ of Australian comic books. From 1946 to 1958, American comics were nearly impossible to buy due to government-imposed import restrictions on items to be paid for in United States dollars. Restrictions remained in force until the late 1950s, so American comics did not re-appear on local newsstands until 1959.

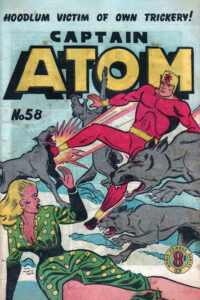

Australian publishers such as K.G. Murray Publications decided to print their comics in colour. One of the new titles introduced was Climax, which showcased the talents of several Australians who had been seen in colour for the first time. Atlas Publications struck back with their contender in the colour stakes, Captain Atom [Figure 1]. Scripted by John Welles and drawn by Arthur Mather, this character was an unabashed combination of another two captains, Triumph and Marvel – where twin brothers transformed by uttering the word ‘Exnor!’.

Due to Australia’s small market and lack of export options, it was near impossible for local publishers to sustain the type of circulation required to support the cost of colour reproduction, so, in just two short years, the colour experiment was dropped. While the colour was gone from the comic book sector, the reprints of American comic characters stayed. It was a fateful decision that culminated in an unwanted outcome. To reduce expenses, local publishers reproduced many American titles, including Batman and Aquaman, to the point that few publications were reprinted.

So by the late 1950s, the reprints had taken over, displacing an entire industry and leaving only a handful of Australian artists, many of whom went ‘underground’. The American reprints responsible for this extinction were about to be put out of business. With their narrow, black-and-white efforts, the reprint publishers could not compete against the sharp-looking, brightly coloured comic books that were directly imported from the United States and sold for the same price. And with that, the Australian comic profession, once again, became virtually irrelevant. It would take another forty years before the industry attempted a sustained recovery.

The golden age of Oz cartooning is in decline and has just about ended.

Vane Lindesay

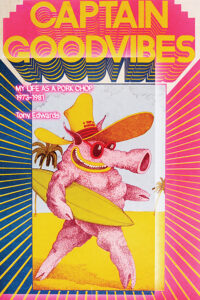

The only comic of note that came out of this cultural wasteland was Captain Goodvibes in 1973 [Figure 2], which featured a pot-smoking, motorcycle-riding pig. This unflattering publication was the pinnacle of Australia’s ‘Silver Age’ of comics. A renaissance of sorts began in the late 1980s thanks in part to the growth in comic book shops and the dawning of fan-based pop culture. The advent of digital delivery, both in p-book and e-book format, and the proliferation of comic conventions [such as Armageddon, Supanova, Oz-Comic Con, and ComiXpo] have helped contribute to a resurgence in locally made and manufactured material. Yet, even with this stimulus and the vast array of talent and resources available in Australia, why is our modern comic book industry so enervated?

Captain Goodvibes, the thinking man’s fuckwit, a lovable abomination, a cartoon pig who became a cult hero to a generation of Australian surfers. Valiantly battling the three-headed Hydra of sobriety, employment and authority, the Pig of Steel took bad taste, substance abuse and pointless revolution out of the gutter and onto the beach, souring young lives and stealing the promise of a bright future from the tiny hands.

Tony Edwards creator

Despite the renewed interest, Australia’s major magazine publishers consistently refuse to entertain the idea that there is a market for domestically produced comics. The cost base for creating a significant publication is not excessive, and the market certainly exists, so why is there reluctance? As the industry struggles to gain a foothold against the DC, Marvel, and Image monopolies, could an Australian ‘superhero’ garner enough support and attention from the reading public to further stimulate the local comic book industry? What is certain, if there is to be another ‘Golden Age’ of comics in Australia, it won’t be the same as the last one. We must look for different things in different places to develop any worthwhile, contemporary and long-lasting movement.

Lindesay, V 1970, The Inked-in Image: A social and historical survey of Australian comic art, Hutchinson, Richmond.

Ryan, J 1979, Panel by Panel: A History of Australian Comics, Cassell, Sydney.